A Ballad Lovers Tale: The Famous Flower of Serving Men

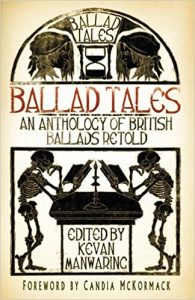

Back in June I was delighted to have a story published in this collection edited by Kevan Manwaring, Ballad Tales. Kevan’s been getting seriously into ballads in recent years, in part due to his PhD research

, and in part due to his folk singing, balladeering partner, Chantelle Smith. I was thrilled to be asked to contribute because I’ve loved ballads since I was but a wee lass. My stepdad, weary of listening to the likes of Wham, Duran Duran and the Thompson Twins, decided that it was time to reintroduce me to folk music. Of course, I’d been listening to folk music since I could walk, going to festivals and to see the Morris (back in the day when I had to sit, grumpy, outside the pub because under 12s were not allowed in!), but then, aged c. 12, I was a little disenfranchised. So, he played me fairy ballads – Tam Lin by Fairport, Thomas the Rhymer by Steeleye. It was a cunning plan to hook a girl already lost in fantasy fiction … and hooked I was. I still have the tapes I made back then – Ballads 1, 2, 3… And yes, I do still have a tape player on which to play their slightly stretched and wobbly glory! I’d love to recreate those tapes as playlist now, but sadly some of the songs, such as another Tam Lin by the Jumpleads, a ‘new wave’ band plying ‘rogue folk’ from the early 80s, are just simply not out there…

Back in June I was delighted to have a story published in this collection edited by Kevan Manwaring, Ballad Tales. Kevan’s been getting seriously into ballads in recent years, in part due to his PhD research

, and in part due to his folk singing, balladeering partner, Chantelle Smith. I was thrilled to be asked to contribute because I’ve loved ballads since I was but a wee lass. My stepdad, weary of listening to the likes of Wham, Duran Duran and the Thompson Twins, decided that it was time to reintroduce me to folk music. Of course, I’d been listening to folk music since I could walk, going to festivals and to see the Morris (back in the day when I had to sit, grumpy, outside the pub because under 12s were not allowed in!), but then, aged c. 12, I was a little disenfranchised. So, he played me fairy ballads – Tam Lin by Fairport, Thomas the Rhymer by Steeleye. It was a cunning plan to hook a girl already lost in fantasy fiction … and hooked I was. I still have the tapes I made back then – Ballads 1, 2, 3… And yes, I do still have a tape player on which to play their slightly stretched and wobbly glory! I’d love to recreate those tapes as playlist now, but sadly some of the songs, such as another Tam Lin by the Jumpleads, a ‘new wave’ band plying ‘rogue folk’ from the early 80s, are just simply not out there…

The ballad I chose certainly is out there, and remains a favourite ever since those early days more than 30 years ago. My stepdad wasn’t convinced I’d like Martin Carthy straight away, thinking his singing and playing rather an acquired taste for a Duran Duran aficionado, but I loved him immediately. My stepdad played me his own favourite, and it was this ballad, from Carthy’s album Shearwater , 1972 , that I chose to retell for the Ballad Tales book: The Famous Flower of Serving Men.

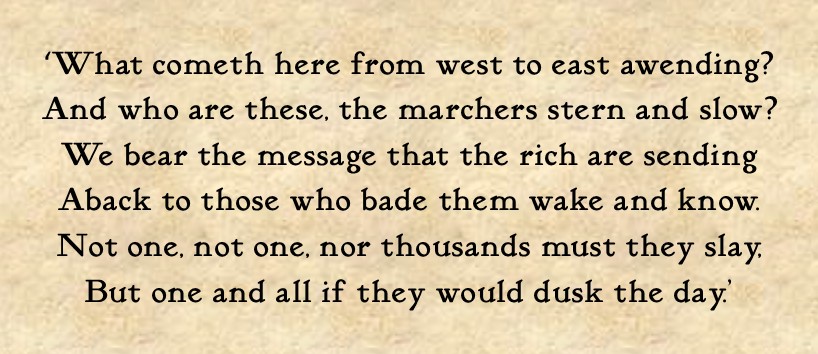

This is a typical border ballad. It’s bleak, very bleak. To me, Carthy’s first lines were incredibly powerful:

My mother did me deadly spite

For she sent thieves in the dark of night

Put my servants all to flight

They robbed my bower they slew my knight.

They go on to kill her baby, steal everything and wreck the place, and she, in fear and grief, cuts off her hair, puts on men’s clothes and reappears as Sweet William. William goes to court, becomes the eponymous Serving Man to the king – a Chamberlain, the man who looks after the king’s household – and the king, well, he’s rather disturbed by his feelings to the young man. One day he goes off riding in the forest, and as you do in ballads, gets separated from his friends chasing a white hind and has a magickal hexperience with the spirit of the dead knight in the form of a dove, which causes the king to race home, kiss the boy/girl and then catch her mother and have her burnt at the stake… For me, it was the otherworldy white hind and the white dove that really made the song.

We had two versions of it the song at home. The other one was one a Chris Foster album, Layers , and that one offered an ending that I found interesting. When the mother has been burnt etc., the king proposes, but the girl refuses:

Oh no, Oh no, Oh my lord” said she

“Pay me my wages and I will go free.

For I never heard tell of a stranger thing

as a serving man to become a queen.

I loved that she doesn’t go for the so-called fairy tale ending, but rather rejects the king and goes off to make her living another way. It seemed plausible to me that a woman who’s lived had been so blighted wouldn’t immediately marry the first man to look at her, even if he was the king.

Now, back in those days there was no internet to access, but I got out from the library Child’s Ballads volumes 1 and found out lots of stuff – but not about this ballad, which is in volume 2, which my library didn’t have. So it was some years later when I discovered that the things that I liked best of all in the ballad were, in fact, made up! In the ballad the girl is simply overheard singing about her background (an elementary mistake!) by a ‘good old man’ and she does marry the king! What a con, what a cheat! Although Foster is actually following the singing of an English singer, Albert Doe of Bartley in Hampshire, recorded in December 1908. When reworking the ballad for the 21 st century I decided, sod it, that I would keep in those 20 th century alterations.

The ballad first appears in Percy’s Reliques of Ancient Poetry , 1765 as ‘The Lady turned Serving-Man’ [i] – to which Percy admits ‘improvements’ have been made (‘excerable’, says Child) – and in this version, it doesn’t appear that the mother did it, but unspecified ‘foes’. This then is suggestive of a more familiar and realistic story of border raiding and feuding – the woman only ‘scant with life escap’d away’.

This is then unpacked further by Walter Scott in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border , 1803 [ii]. Scott had another ballad, ‘The Border Widow’s Lament’, in his collection, which he describes as a ‘fragment’.

Here’s Chantelle Smith singing the ballad as part of her Ballads in the Borders and Beyond project this summer:

This ballad Scott says he himself heard sung from recitation in the Forest of Ettrick. He says it ‘is said to relate to the execution of Cockburne of Henderland, a border freebooter, hanged over the gate of his own tower, by James V’. Cockburne was, by all accounts, not a very nice man. A border reiver (raider), he, according to the ONDB ‘enjoyed a laird’s status in the Scottish borders, holding the twenty-pound land of Henderland and Sunderland in Peeblesshire and Selkirkshire, with tower and chapel. He preferred, however, to make his living from theft, blackmail, and collusion with Englishmen during the minority of James V.’ [iii] When James V turned 17 he was able to free himself from his advisors, and set about stopping the activities of these border lords. William Cockburn was killed about 1530, strung up, the tradition goes, from his own tower. His widow Marjory, Scott suggests, is the widow in the song:

I took his body on my back,

And whiles I gaed, and whiles I sat;

I dig-g-‘d a grave, and laid him in,

And happ’d him with the sod sae green.

This is sadly unlikely, as James had Cockburn and the other reivers executed in Edinburgh, but it’s a good story, substantiated by a monument in the wilds near to the tower which reads ‘Here Lyes Perys of Cokburne and His Wyfe Marjory’ – admittedly, probably not the same Cockburn! [iv]

In fact, we can follow the Famous Flower ballad further back than either Percy or Scott knew, though not quite back to the 16 th century. It was written down by the prolific balladeer Laurence Price, and registered in the Stationers Register on July 14 1656. Price wrote 36 chapbooks containing histories, science, wonders etc., and registered at least 62 broadside ballads. Child’s ballad is taken from Price, although he doesn’t acknowledge him. [v] Where Price got it from, however, we’ll probably never know…

My version brings things into the 20 th century, giving the ballad a 1920s gangster setting, not too dissimilar from the border reivers of the 16 th century…

Notes:

[i] Percy, Thomas, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (George Bell and Sons, 1876), p. 162

[ii] Scott, Sir Walter, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border , volume 3 (Robert Cadell, 1849), p. 94-97

[iii] Henderson, T.F., ‘Cockburn, William, of Henderland ( d. 1530)’, rev. Maureen M. Meikle, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5776, accessed 31 July 2017]

[iv] Inspired by Scott, an unknown author penned a poem in 1832 as part of their collection Iolande, a Tale of the Duchy of Luxembourg , with a somewhat biased account of ‘Pier’s’ betrayal by the king…

[v] Palmer, Roy, ‘Price, Laurence ( fl. 1628–1675)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22759, accessed 31 July 2017]

The post A Ballad Lovers Tale: The Famous Flower of Serving Men appeared first on Palace of Memory.